Khadi is not a mere fabric. It is a fabric that embodies the past, present and future worldview. A symbol of the Indian textile, it is a fabric that continues to amaze and inspire people worldwide.

The name khadi is derived from ‘khaddar’, a term used for handspun fabric in India, Bangladesh and Pakistan. Khadi is usually manufactured from cotton, but contrary to popular belief, it is also made from silk (khadi silk) and woollen yarn (khadi wool).

Khadi has a long and winding history in India. Archaeological evidence suggests that the art of hand weaving and hand spinning has been known to Indians since the Indus Valley Civilization. Terracotta spindles (for spinning), bone tools (for weaving) and figurines wearing woven fabrics suggest that Indus Valley Civilisation had a well-developed and flourishing system and trade of Indian Textiles. The famous stone sculpture excavated from Mohenjodaro wears an elegant robe with motifs and patterns still prevalent in modern Gujarat, Rajasthan and Sindh.

A few 5th-century paintings at Ajanta caves in Maharashtra depict women separating cotton fibres from seeds, which leads to the conclusion that the women are familiar with the art of spinning cotton into yarn.

The earliest written description of cotton textiles in India comes from ancient literary texts. Greek Historian Herodotus in 400 BC, in his travel accounts, noted that in India, there were “trees growing wild, which produce a kind of wool better than sheep’s wool in beauty and quality. The Indians use this tree wool to make their clothes.”

Another literary evidence is found in Chanakya’s Arthshashtra; wherein there is a mention of spinning yarn out of wool, cotton fibres, hemp and tree bark and giving them to artisans to produce goods.

The trade routes established by Alexander the Great and his successors introduced cotton to parts of India and Europe. This led to the flourishment of Indian cotton and muslin cloth. By the medieval era, European demand for Indian muslin had skyrocketed. It was the most preferred fabric across Europe and Asia. Known for its fine translucent quality, every muslin yarn has a thickness of 1/10th of a strand of hair.

With the advent of Portuguese in India, linen-like calico fibres and chintz were introduced to Europe. These hand-woven fabrics soon became popular with the common public due to their comfort, durability and low cost.

Worried about their local mills due to the ever-growing popularity of Indian handspun fabrics, England and France enacted laws to ban the import of chintz. On top of it, they flooded the Indian market with cheaper fabrics produced in European mills. The establishment of the textile mills in Bombay resulted in a further dip in the production of handwoven khadi in India. Millions of weavers across India lost their livelihoods as machine-made textiles took over the Indian market.

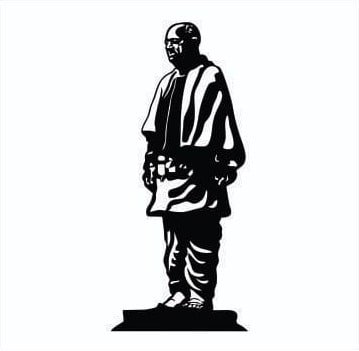

The decline of the handwoven fabric continued until it was single-handedly revived by a bespectacled man who wanted to make the charkha a symbol of India’s regenerative economy. Gandhi didn’t just restore the declining Khadi industry of India, but he made the humble hand-spun fabric the symbol of all things swadeshi.

When he encouraged the people of India to boycott foreign goods, spin their own yarn and wear khadi, he was encouraging them to rediscover their pride in their heritage while at the same time supporting their rural brethren.

“If we have the ‘khadi spirit’ in us, we would surround ourselves with simplicity in every walk of life. The ‘khadi spirit’ means infinite patience. For those who know anything about the production of khadi know how patiently the spinners and the weavers have to toil at their trade, and even so must we have patience while we are spinning the thread of Swaraj”, Gandhi says in a famous quote.

This masterstroke statement by Gandhiji intensified the impact of the Swadeshi Movement beyond the rarefied circle of educated elites and helped it reach the masses.

In 1925, the All India Spinners Association was established to propagate, produce and sell khadi. They worked tirelessly to improve the technique of weavers spinning khadi, spread awareness, and provide employment to weavers across India.

Post-Independence, the Indian government established the All India Khadi and Village Industries Board which later became the Khadi, Village and Industries Commission (KVIC). The KVIC is involved in the development of the Khadi industry in India.

As India entered the 21st century, designers from all walks of life started experimenting with versatile fabric. From dresses and jackets to bridal lehengas and deconstructed local silhouettes, several leading designers have taken on the fashion challenge to reinvent the humble fabric into high-fashion wear.

As part of India’s warp and weft, khadi continues to be exceptional in many ways. As the world moves towards industrial fashion, this fabric of freedom continues to spin incomes for the rural poor while reminding the country of its legacy of sustainable living and self-reliance.